Why do I feel so blue? It’s not just you

September 29, 2020

A blackout of communal gatherings, school pep rallies, sports meets, cinema ticket lines, award ceremonies, family reunions, esoteric conferences, friend hangouts, child playdates, date nights…COVID-19 eradicated the quasi-socialite in every individual. Whether reserved or outgoing, intra-or extraverted—it made no difference to the big bad virus.

Doubtless, it certainly made a difference to sophomore Dakota Helgren. Not one to consider mental health a priority, Helgren never evaluated the reasoning behind her stress or anxiety. In fact, it was “second thought.”

However, the pandemic allowed her to reevaluate the root of these stressors on her health; rather than route herself for upcoming tension and distress, she determined mental health had to be her priority.

With self-isolation affecting mental health, “Quarantine…gave me the time to make sure I am happy,” according to Helgren, relying on physical activities such as running and swimming to strengthen her mental health, as well as painting and family board game nights.

But locked up in the house for six months is prone to result in boredom. Indeed, the main challenge, according to Helgre, was discovering new ways to spend all the free time.

“During quarantine, when I’m bored or need something, I ask myself what I feel like doing or what it is I need,” said Helgren, adding accordingly this evaluation of needs and wants allows her to take advantage of the situation (“as long as it’s COVID-friendly and safe, of course”).

Unlike Helgren, psychology teacher Amanda Augustine could not prioritize her mental health for different circumstances. Home with two small children, an absent husband during the day commuting to and from work during the pandemic, Augustine was “irritable…isolated and frustrated.”

While an advocate for mental health as the sponsor of the I Need a Lighthouse Psychology club, she neglected health in order to be a caregiver to her children, no alone time in sight.

Moreover, Augustine is self-aware of the impact mental health may have on her ability to perform her roles as “mother and teacher and friend.”

Regardless, she was not accustomed to the lockdown weight she and her prescribed roles pressed upon her psyche.

“Initially…I thought quarantine would be great,” said Augustine, her introverted characteristics ostensibly prone to excel in self-isolation. “I quickly realized I would not actually be alone ever . . . since I have two small humans who are always around and seem to expect me to care for them and feed them and constantly demand my attention.”

In order to change this mindset, Augustine determined to devote time to herself throughout the day— “even if it is [was] just a walk around my neighborhood.”

Likewise, English teacher Stephanie Coari struggled with creating a balance between caring for others and herself.

“The nature of [teaching] is caring for and taking responsibility for other people. It leads us to worry, to overcommit our schedule, and to look after everyone else without consideration for our own needs.” Furthermore, Coari added she was beginning to “break those habits” in order to satiate her health and fulfillment of wellness.

Not everyone is willing, however, to take a moment from their day to arrange some time away from predominant stressors. For senior Ashley Szalkowski, that stressor is school work.

“I am very goal-oriented,” said Szalkowski, an individual who is not one to consider a walk around the neighborhood. “I am more concerned with whether or not those goals get done.”

But quarantine changed the paradigm of Szalkowski’s habitual routine, no longer stressing over school work but rather how to remain productive.

“The biggest challenge has been finding motivation to be active. In the beginning of quarantine, we couldn’t even go out except for necessities, so it felt like there was nothing to do. I returned to things like books, puzzles, and online games rather than going out with friends.”

Quarantine offered relief from mental pain, an opportunity to reconsider how mental health has an effect on her daily life.

Coari too had to reevaluate her health in order to necessitate self-care and mental health: “Having several months at home provides a lot of time to think!”

Moreover, Szalkowski stressed that resources shared via the Internet during COVID-19 “helped me to better understand what others were going through,” as well as allow her to assess her own feelings during the pandemic.

“As society started to focus more on mental health, I was able to turn my own focus in that direction, as well.”

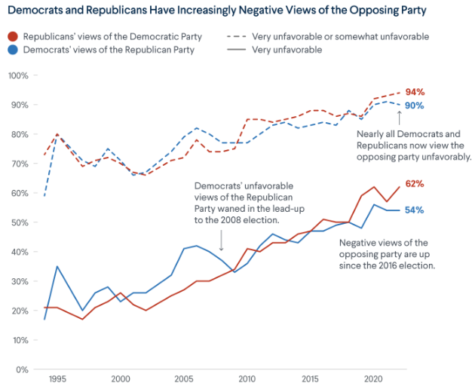

This shift in direction about normalizing the conversation surrounding mental health is a facet of Augustine’s role as teacher. Acknowledging the stigma surrounding mental health, in which students, teachers, and parents tend to see the topic as a sign of weakness, she rather encourages and reinforces the notion that society should address mental health.

This stigma is a “cultural norm that talking about mental health and illness (depression, anxiety, therapy, medication, and other topics related to mental illness) is not appropriate or is even shameful.”

With this shunning of a taboo topic, “Those who are suffering don’t see or hear anyone else sharing so they feel they are completely alone in their experience (even though they are not). “

Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on its website divulges information regarding coping with mental health during the pandemic. Background, social support from family or friends, financial situations, health and emotional background, community, etc. may affect one’s reaction to stress during the pandemic, according to CDC.

With the stress of fulfilling the role of parent, teacher, and student, stressors are bound to take a toll on mental health.

Therefore, “Keep your mind and body active,” says Coari. “It’s too easy to isolate ourselves–it was easy to do that before quarantine…Figure out: ‘What could feed my health?’ and [find] the time to implement it.”