Last Christmas, I got a scratch-off poster of the 100 best movies of all time. I taped it up in my closet, directly in my line of sight when I pick out a shirt for the day, which forced me to watch more movies in a New Year’s Resolution sort of way. While I’ve only made it through 19 of the 100, I found a few movies that I loved: the French romance of “Amélie,” Robin Williams’ “Good Will Hunting,” Javier Bardem’s thrilling performance as Anton Chigurh in “No Country for Old Men,” and the stock answer of film-expert pretenders (like myself) “Pulp Fiction” to name a few. There were also a few I didn’t enjoy as much, the twist ending of “Fight Club” didn’t make sense to me, I was asleep by the time “The Breakfast Club” rolled to credits, and I thought “The Matrix” was trying just a bit too hard.

I may not be the foremost authority on the subject, but over the past year I’ve grown to appreciate the artistry and creativity of what I feel is a great movie. I don’t, however, have much appreciation for the recent output of the movie industry. Movie titles increasingly feel like a manifestation of commercialization, storyless, heartless cash grabs, picked by profit-motivated Hollywood business executives.

Obviously, the situation isn’t as dire as that sentence made it out to be. There are still many great, recent movies, but to some extent, an amount which is up to one’s personal interpretation, the sentiment stands.

Namely, movie studios seem to exclusively release prequels, sequels, remakes, and franchise additions, a philosophy propagating that every movie that has been successful in the past needs to be reheated like a plate of soggy green bean casserole to be tossed out for some more money making.

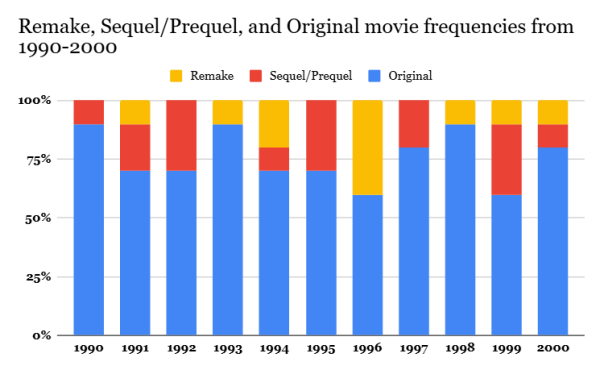

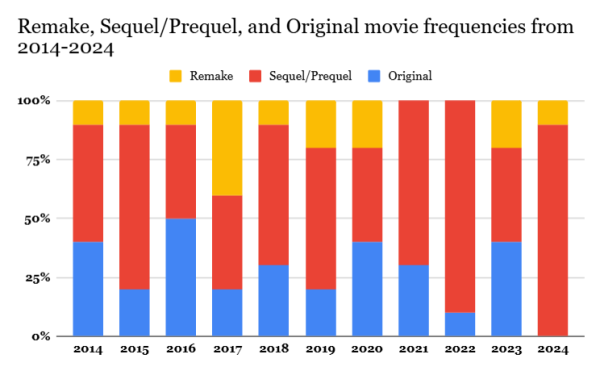

Take these graphs for example (data from IMDB). They show the top ten highest grossing movies from two 11-year periods, 1990-2000 and 2014-2024, interspaced by a period of 13 years. The blue portion of the graph, the number of original movies, makes up 75% percent of the movies in the 1990-2000 period, while only constituting 27% of the total in 2014-2024. In addition, a majority of the “original movies” in the latter period were members of a franchise, like DC Comics or Marvel, using universes and characters already in the public consciousness.

This isn’t a perfect representation of the trends in the movie industry, but it does confirm a general idea. Movie studios have made, at times, dramatic steps away from creating original movies, directing their attention towards using pre-existing successful concepts instead.

The crux of the issue is that sequels, prequels, remakes, and franchise additions are extremely successful. Since 1980, the average original film made back 2.8 times its budget, while the average sequel film made back 4.2 times its budget, according to the book “You Are What You Watch” by Walt Hickey. By making an original movie, movie studios are taking on more risk that the movie flops, by remaking a concept that they know already works, movie studios have an increased chance of making back their money.

In parallel, the movie industry as a whole has had a bit of a hard time. The COVID-19 pandemic, like in many parts of our collective lives, shattered the industry in 2020. As people stayed home and blockbusters were delayed due to collective panic because of the virus and to abide with public health guidelines, movie theaters hemorrhaged money. The largest theater chain, AMC Entertainment, alone lost 77% of their revenue, $4.6 billion, and box offices lost 80% of their combined revenue despite a successful first three months of the year. The hole punched in the movie industry by COVID may have been temporary but filling it in has proved a difficult task.

Attendance and earnings are increasing at movie theaters but remain below pre-pandemic levels just under five years later. Part of this trend may be explained by the rise of streaming services. Eighty-eight percent of US households have at least one streaming service, per the Leichtman Research Group, a percentage that continues to grow. The prevalence of streaming services has further discouraged consumers from watching movies at brick-and-mortar movie theaters, by waiting for the movie to be released onto streaming services they can save money (see below) and maintain a similar quality of experience.

The average movie ticket today is $10.78, significantly more than the beginning of the century’s inflation-adjusted $7.82. When you account for food and drink, often the costliest part of going to the movies, the prices can increase even higher; the staple of the movie theater experience, popcorn, only costs about 90 cents to make, but it costs, on average, $7.99 at the movie theater, a 788% markup.

Why go to the movie theater when it’s expensive and you’re used to using a far more convenient, intimate, and easy way to watch movies? Why watch a movie right now in the theater when you can wait a couple months and half-watch it on your couch while you scroll through Instagram? The overall technological and economic trends make it ever more important that the movie makes enough money to support itself, and through sequels, movie studios have found a safe space to hide out the storm.

Out of the many attributes a movie can have, creativity is the most important one for me. If not for the exercise of child-like imagination to make something relatively novel and special every once and a while, why make stories? Sequels, prequels, and universe expanders can always be good movies, but if they compose the entire slate, it can become stale and repetitive. I understand the motives of movie studios, and none of this is pointed at any singular entity or person, because the titanic size of an industry can only be turned with similarly colossal systematic changes, but the talent to make great, entertaining art is there, i.e., some of the best TV shows of all time have been made in just the past few years. I hope the necessary course corrections will be made to prioritize standing out over monetarily motivated falling in line.

Tomtom • Jan 15, 2025 at 5:32 pm

Absolutely great article and very well written. I agree with thoughts of the author. So many of the sequels are predictable. I often wonder why a remake of an already great movie is done. Rarely is the remake better than the original. To avoid repeating what the author has already stated my hopes are that the movie industry strives to promote creativity and originality.