The future of the Republican Party: A post-Trump era

Image from Web Urbanist

March 14, 2021

By Sophia Meagher and Ruby Hoffman

What if in 2024, American voters have not just the options of a Democrat or a Republican for president, but a third major political party candidate as well? What would the effects of a third major political party be on American politics? Indeed, within the next few election cycles, we may see a split Republican party―the end of an age of republican relevance.

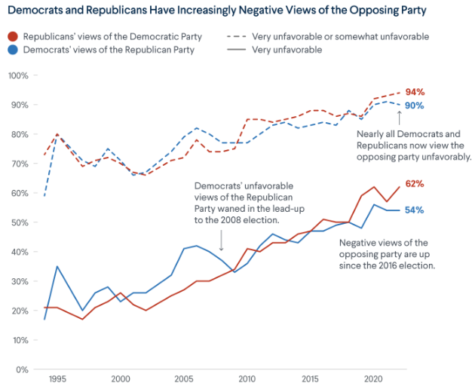

According to a recent Gallup poll, 62 percent of Americans believe a third party is needed—increased from the 57 percent of U.S. adults who answered in the affirmative on the same poll conducted back in September. This data, combined with divisive events such as the riot on the Capitol on Jan. 6 of this year, suggest that a significant change in our political system may be on the rise.

Although former President Trump indicated at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) that he would not create another party, political scholars are not so sure. On Sunday Feb. 28, former President Trump took the stage at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) and asserted the very same baseless election claims that led to the riot on the capitol about which division in the party was spurred. Where does the party go from here?

Emerging from a scandal-plagued, one-term presidency, former President Donald J. Trump escaped Senate impeachment conviction for a second time on Feb. 13. In leaving office on Jan. 20—having brought with him a vast sector of the Republican voter base—Trump presented republicans with uncomfortable notions of true core American ideologies and an even more pressing responsibility to respond to such notions with a firm, decided stance.

Republican Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, a long-time Trump ally, stated in a speech following his vote for acquittal of the former president, about the Jan. 6 insurrection of the U.S. Capitol: “There is no question that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of that day. The people who stormed this building believed they were acting on the wishes and instructions of their President. And their having that belief was a foreseeable consequence of the growing crescendo of false statements, conspiracy theories, and reckless hyperbole which the defeated President kept shouting into the largest megaphone on planet Earth.”

He proceeded to contradict those claims with an assertion of the unconstitutionality of Senate conviction, saying that “impeachment, conviction, and removal are a specific intra-governmental safety valve. It is not the criminal justice system, where individual accountability is the paramount goal… We have a criminal justice system in this country. We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one… I believe the Senate was right not to grab power the Constitution does not give us.”

Even so, seven Senate Republicans voted to convict, making for a 57-43 majority conviction vote, but falling short of the two-thirds majority required to remove Trump from office. Senators Richard Burr of North Carolina, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Mitt Romney of Utah, Ben Sass of Nebraska, and Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania all took their stand against what many have come to refer to as “the Big Lie” of election fraud, and Trump’s role in inciting the riot. Furthermore, these Republicans and others like them have realized the bite Trump has taken from traditional Republican values.

It is natural for parties to change and evolve over time, and it’s not uncommon for a single person to dominate that party, like Ronald Reagan in the 1980’s. However, where the two Republicans differ is while Reagan inspired “Reaganism,” a set of policies and ideologies that reflected the GOP’s deeper values, “Trumpism” depends entirely on whatever whim Trump is feeding on at the time. Republicans such as the ones who voted to impeach Trump are sick of this blind fanaticism for Trump, especially due to Trump’s brash rudeness, policy failures, and failing to support traditional Republican values.

But, where does that put them in the party at large?

Trump has released multiple statements indicating that he will back Republicans running 2022 reelection campaigns who supported him in the conviction trial by their acquittal votes―presenting the seven conviction voters with a large mountain to climb to retain support within the party.

In stark contrast to the anti-Trump conviction voters and like-minded Republicans, conspiracy theorists like the recently deceased Rush Limbaugh, a controversial conservative radio personality awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom under the Trump administration, leave behind an ash of conspiratorially backed pronunciations of Republican righteousness and Democratic devilry. This poisonously pervades party ideology and emboldens conservative theorists today as they assert their own outrageous pronunciations.

Indeed, many of Trump’s hard-core supporters are involved with the social media conspiracy web called Q-Anon. The group’s conspiracies include baseless notions such as that liberal politicians are leading a global child sex traffiking ring; hence, you will often see a #savethechildren attached to associated posts. Individuals involved claim to be obtaining this information from a high-ranking government or military official called “Q,” who leaves them clues as to what liberals and some disaffected Republicans are supposedly plotting in the government. A recent star in both mainstream and conservative media, freshman Georgia house representative Marjorie Taylor Greene was recently stripped of her house republican committee roles on account of repeated assertions of extremist theories affiliated with Q-Anon―most notably a commission to her supporters to assassinate the Speaker of the House, esteemed Democrat Nancy Pelosi, on conspiracy-based counts of treason.

It remains to individual actors―such as the seven breakaway Republican Senate conviction voters and thinkers like them―to demonstrate what acting in conscience, against the tide of public opinion and self interest, can mean in the context of such corruption.

Can seven breakaway voters emerge leaders of a new party? Do they have broadscale support?

Individual Republican thinkers at the Lincoln Project, a foundation of anti-Trump republicans which levied harsh ad campaigns against the prospect of Trump’s reelection, send a promising signal to that end. Such notable Republican figures as Cindy McCain have backed these ad campaigns, and Gold Star military families have participated in fueling support, as demonstrated in a video-ad quoting President Trump referring to soldiers who have died in combat as “losers.”

Can the impact of such opposition to “Trumpism” sway support to such an extent that a third party emerges?

In truth, for most of America’s history, our politics have been dominated by two parties; moreover, the only time that a third party has uprooted a major political party was in the 1850s, when the newly formed Republican party took the place of the major party of the Whigs and propelled Lincoln to presidency. It is far more difficult by modern political processes to start new political parties than it was 160 years ago, because it is extremely difficult for political candidates outside of the major parties to even get on the ballot.

Ross Perot, the last “successful” third-party candidate to make it to the general election, only won about 19 percent of the vote in 1992. The impact of such support is not meritless; in fact, some hold that Perot’s success in 1992 was a major contributor to incumbent George H. W. Bush’s loss in that election—where many Republican votes that would potentially have gone to Bush were directed to Perot instead. However, such claims are disputed. In many Republcan-leaning regions and states, Perot did very well. However, he also drew many votes in more Democratic areas. Additionally, Perot voters were very demographically similar to Clinton voters. A lot of analysis suggests that Perot likely drew equal support from both Clinton and Bush—not mostly from Bush. While Perot probably did cost Bush electoral votes in some states, it is impossible to say whether or not Perot’s position on the ballot cost Bush the entire election.

In any case, Perot’s situation raises questions on how a Republican split might lead to Democrats consistently winning elections. If the Republican party splits, then it will be much harder for either branch of the former Republican party to garner enough support to beat the Democrats, who would still be retaining roughly the same number of voters. This could lead to a period in which the Democrats would likely have majorities in both the Senate and House of Representatives, as well as more easily winning the presidency. However, if the remainders of the Republican party were to survive this period, it is highly possible that the United States could see a viable multi-party system.

So, what is the future of the party system in the U.S.? Will we see a three party system take hold in our lifetime?

We encourage you to share your thoughts in the form of a comment, a virtual “letter to the editor,” below.